Dealing with Desperation at…Home

She held out a dirty and partially crumpled piece of paper at me, and she pleaded, she wailed, she begged.

“What should I do? What will become of my son? My little innocent boy whose only crime was to be born poor!”

The paper in her hand was not an arrest warrant but it might as well have been, indicting me, charging me with a crime I know I’ve committed, always committed and probably always will commit till the end of my days, and then my crime will live on in my heirs after I’m gone, so I will continue to commit it from the grave.

Her face was swept with ridges of pain like many sand dunes on a desert of suffering. I guessed the faded leathery hide through which her eyes peered and mouth made pitiful noises had been beaten by the sun for perhaps forty years, though she looked a good fifteen years older. Dark and cracked, hers was a face that tells the story of hard living, a life of uncertainty and less. Less food. Less mercy. Less pity. Less love. Less everything. Over time such a life leaves many people less human, which only exacerbates and accelerates the downward spiral that is the signature of poverty the world over.

When I look in the mirror, I know I’m guilty. The plump, coddled, wrinkle-free face looking back is so obviously guilty. Again I glance down at the paper in her hand. One of the crumpled corners points an accusatory finger up at me. “Him!” – “That’s all it needs to say, like the witness testifying in court – “It was him!”.

Naturally this is making me uncomfortable. I wish this woman wasn’t standing in front of me, wasn’t reminding me of my guilt. I’m not an expert criminal yet. Even though I always get away, I feel bad about it. Of course, the crime I speak of is being somewhat wealthy in a world full of crippling poverty, and it always weighs on my conscience. So I look away, side step the beggar woman and walk away. Everyone else ignores the poor and gets away with it, so why should I be the fall guy? I mean if our whole network of criminals was to institute a guilt fee to benefit those born into poverty, like a homeowners’ association has membership dues, I’d be fine with it. I’d even go to the meetings and lobby for a high fee, but I’m not fine with footing the bill by myself. I’m not a fool………although sometimes I have doubts.

Mistake #1 – because of my inexperience dealing with the truly miserable, I had hesitated early in our dance. Before I turned away, her beseeching eyes had caught the look of guilt and discomfort on my face. She knew she was barking up the right tree. This tree will shed some fruit. She cut off my retreat, pleading even harder, trying to shove the paper into my hand – “You have been served” said the paper. I knew I had fucked up. I should have shut her down in the first second as soon as she walked up to me. I’d seen many people have success with “Shut up and get lost! Bother someone else!”. A quick soulless admonishment like that usually got rid of them. No fruit here lady, no humanity either. Bugger off now.

Now I had to pay for my fuckup. It’s only fair. It turns out I am a fool after all, but I’ll do better next time. I learn from my mistakes. I’ll be less of a fool next time.

Fool me once – shame on you. Fool me twice – shame on me.

Actually, I’m kind of relieved. I am probably tens of thousands of times wealthier than this woman. I shall save her sick son, and it will cost me a pittance. To be a hero without any real effort or cost – isn’t that the dream? Committed to this new course of action, I finally face the pitiful, bent-over woman, barefoot and in dirty clothes. “What do you need?”

I already knew the back story from her earlier wailing. She was alone. She had no one except her little boy who was deathly ill. She had used her last rupee to take him to the hospital where the doctor had prescribed medicine, but she had no money to buy it. So she was standing on this street corner at night, close to the pharmacy, prescription in hand, praying to Allah that someone will help save her son.

Her hysterics subsided now that she finally had someone paying her problem attention. She held out the piece of paper, “Here”. The streetlights weren’t very bright and besides I can’t read a doctor’s handwriting to save my life, so I asked more directly “How much does the medicine cost?”

I knew how cheap drugs are in Pakistan, Asia in general really, so I knew it wouldn’t cost much, and I decided immediately that I’d cover the full cost of the medicine. When it’s so cheap, why not cover the whole thing? I wanted the satisfaction of knowing I had single-handedly saved her son. Contributing is for chumps!

“1,430 rupees”

“1,430 rupees! That’s very expensive! What kind of medicine is this?”

“I don’t know son. I’m poor and uneducated. I only know the doctor said this will save his life. His fever is very bad. I don’t think he will survive the night if he doesn’t get it.”

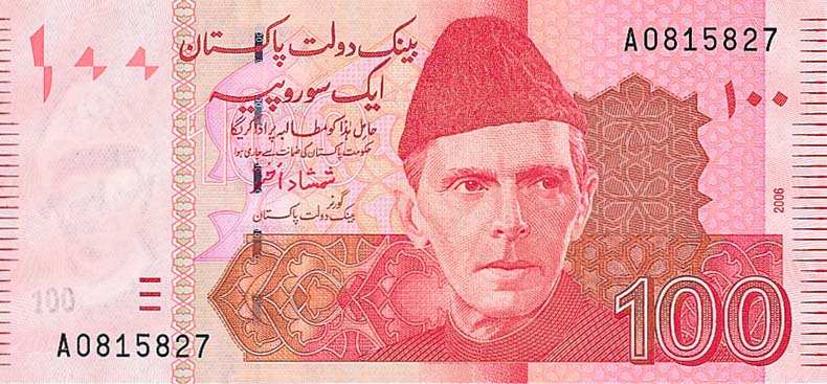

Realizing the size of the hole this lady was in was considerably larger than I had imagined, I quickly decided I couldn’t be her knight in shining armor, and resigned myself to contributing hero (a.k.a. chump) status. “Alright fine, here’s one hundred rupees.” I dug in my pocket and held out a crisp red bill. A red Quaid looked up at me from the note. He said nothing but his expression said “What are you doing?”, which struck me as odd. I had hoped he would be proud of both our roles in my good deed. But I’m a rational man, although sometimes I have doubts about this too, so I resolved not to overthink the meaning behind the facial expression of the dead founder of Pakistan on his tiny red portrait with 100’s on the corners.

She didn’t take the money. Acting like this generous offer was an affront, she exclaimed “What will I do with a hundred rupees? My son is dying! He needs the medicine! I’m not a beggar! I wouldn’t beg in a million years but I have no choice. You’re a rich man! PLEASE! Save my boy’s life! I’m begging you! I will pray to Allah for your long and prosperous life! Just please save my son! He’s all I’ve got in this world!”

Swayed by her appeal, ashamed of my own stinginess, and furthermore feeling inadequate because I didn’t have much money on me, I took out all the cash I had, some three hundred rupees, and tried to hand that to her. But she again declined. Holding the prescription paper out to me again, she pointed to the pharmacy only forty feet away and pleaded me to buy her the medicine. “If you leave I will never get the money I need tonight and my son will die! You’re rich. You’re a good, noble man. I know you can help me.”

Again she had swayed me and shamed me. I was getting agitated. This night was turning out very differently than I had envisioned. The plan had been to pick up some nehari and kabab rolls from Khadda Market, near my house in Defense Phase 5, and now I had been sucked into some strange woman’s desperate race to save her son’s live. Fuck me! (and yes, I realize that makes me sound like an asshole)

I had woken up late that day – Karachi seems to bring out the sloth in me. I spent the entire day browsing the newspaper, or watching torrent-ed movies on my laptop, or lying on my living room sofa staring up at the whirling ceiling fan, at least while the electricity stayed on. A fan that doesn’t whirl is rather dull. My brain was half dead when my mother asked me what I wanted for dinner. “Nihari and kabab rolls” I replied. My father volunteered to pick both up from the market and volunteered me to join him, which was a capital idea as I hadn’t stepped outdoors that entire day. We placed the carry-out order at the restaurant next to the pharmacy after which my father and the cashier, who was probably also the owner, exchanged light hearted conversation and joked around like old pals while waiting for the food.

My father has always gotten along with the common Pakistani better than our own class, “good families” and “old money”, which are really one and the same thing (because in Pakistan, families that have old money are automatically “good”). I think this is because as someone who managed textile mills, cast iron foundries and injection molded pipe factories much of his professional life, he spent a lot of time with the blue collar man (and mind you, blue collar means something very different in Pakistan than it does in America). Since I wasn’t able to follow the conversation between my father and the cashier, something about local politics and how some new politician was small minded and making a mess of things whereas his predecessor had been a man of vision and action, I stepped out into the street for fresh air but instead got ambushed by the hysterical lady.

Now I looked through the restaurant window at my father and the cashier/owner. I took a deep breath. What was about to come next would be tricky and unpleasant. I was going to ask my father for the money and he wasn’t going to be happy about it, not because it’s much money, we’re only talking about fourteen US dollars here, but because he’s felt for some time that I’m a big softy and a bit of a fool in that I trust people too much (a fool and his money are soon parted, especially in Pakistan), an impression that I would be reinforcing.

The biggest difference between us is that he was raised in Pakistan, whereas I was raised across three other countries on three different continents, but all gentler places. I admit I’m a pretty trusting person, and it has yet to catastrophically backfire on me as he has always predicted it would. He on the other hand, will tell you that he is wise to the ways of the world, but especially Pakistan, where street smarts count much more than book smarts. Having been raised the second youngest of eight siblings may have also had something to do with it. Four older brothers sounds rough, even before you get to know my uncles. My father’s guiding principle in life is elegantly simple – “Don’t place too much trust in others for they will abuse it, and always look out for yourself”. This is the mantra he tried to inculcate in me, although it never took. Now I had to convince him to give his hard earned money away to a total stranger.

But then the restaurant’s kitchen door swung open and a teenage boy with a pre-pubescent moustache and a generously oiled and combed back head of hair walked two large plastic bags of nehari and naan up to my father by the counter. Big smile farewells were quickly exchanged and bags in hand, my father turned around and walked out towards me.

I knew he had enjoyed his conversation because he was still wearing his big smile when he got to me, but upon seeing the woman standing expectantly by my side, his smile vanished. “What’s going on here?”

I told him. Predictably, he turned to the woman and told her to get lost. I started reasoning with my father, lobbying for the woman. His face was expressionless as he listened, but I felt certain he was a little disappointed inside. But then the woman decided it would be a good idea to chime in so we could double team her sad story at him, and this my father didn’t appreciate. Turning to face her squarely, he said “Stop your bullshit! We’re not owls! Go make a fool of someone else” and he nudged me with his elbow, pointed to the car and said “Let’s go”. I should mention that owl is “ulloo” in Urdu and calling someone an owl means you are calling them stupid, quite the opposite of the West, where the owl is considered wise.

I felt bad about this treatment of the woman and I protested “No! I’m not going anywhere! Why are you so heartless? Even if you’re not going to help her, which you should, do you have to be so mean?”

“Mustafa, you don’t understand. She’s a fraud! This whole thing is a big drama of hers. There is no son, no medicine. She’s a con artist and she’s trying to make a fool of you. Now let’s go home. We don’t want the nihari to get cold or the naan to get dry. This place makes really good naan.”

At this I lost it a little and started shouting at my own father “How can you say she’s a fraud? How can you know? You didn’t even listen to her! She has a doctor’s prescription. She turned down my offer of several hundred rupees which she would have taken if she was a con artist, and she even asked me to buy the medicine directly from the pharmacy, so she wouldn’t have gotten any money from me, only the medicine. You have a problem you know? You only see the bad in people and I’m sick of it!”

At this my father’s face changed. At first there was surprise. He hadn’t expected my emotional outburst. But he’s a quick thinker, I’ll definitely give him that, and he decided the best course of action was a compromise. He moved to the woman and handed her fifty rupees. “What will I do with…?” she began but he cut her off. “This is more than you deserve. If you don’t leave now you won’t even get this.”

“But bhai (brother in Urdu) over there was already giving me more than fifty rupees!” she protested.

“Forget about that. You’re not getting that. You’re only getting this. Here’s fifty more, ok? Now it’s a hundred. Now please forgive us and bother someone else. Go!”

His voice was loud, his tone harsh, incriminatory. She took one last look towards me, then head bowed in defeat, she took the money and slowly walked away. But if my father thought this had resolved our problem, he was mistaken. I was possibly more upset but also a little more composed, resigned. More sad than angry now I asked “Why couldn’t we have just bought her the medicine? It costs nothing. Please just give her the money and I’ll pay you back when we get home.”

“It’s not about the money Mustafa. She’s a fraud. Do you want to reward a fraud? A liar and a cheat?” he was using a soft placating voice, but this bothered me even more. He was talking down to me.

“You keep saying that but you’re wrong! I’m not stupid! She was genuine and her need was real!”

He smiled, “No it was not. She’s a big fraud.”

“YOU KEEP SAYING THAT!! HOW CAN YOU KNOW?” I shouted. Now I was angry again, almost shaking and again I saw a little shock and concern on his face. We were on a public street in front of a restaurant he frequented (and that apparently made the best naan in the area) and I was coming close to causing a scene, something he obviously didn’t want. Less than a shout but still aloud I continued “You didn’t care to hear her out. You judged her guilty without any proof, and you did it just because it’s convenient for you to call her a fraud, because then you don’t have to shoulder the responsibility to help!”

“Mustafa, I heard her out and it was based on that that I judged her a fraud. Why are you being this way? Is it proof you want? Do you want me to prove she’s a fraud?”

“Yes, because you can’t”

“Do you remember her prescription?”

“Yes”

“Describe it to me”

“It looked like an ordinary prescription! What are you talking about?” I blurted in frustration.

“Didn’t it look old, like weeks or months old? Discolored, crumpled, maybe because it was salvaged from the trash or the street after being thrown away?”

Mistake #2 – I should have paid attention. He was right. All of that was true. The prescription was ancient, the writing smudged to the point it would have been illegible even to a pharmacist, and she had said they had been to the hospital that very day. “But she asked me to buy the medicine directly…” I argued feebly, even though I already sensed, nay, knew, that I was on the losing side of this argument.

My father sensed it too, that this mini-crisis was coming to a close. Mustafa was getting off his high horse (more like falling off), and his misplaced humanity fueled hissy fit was almost over. He smiled “Son, come on. She could buy from one pharmacist and sell to another or more likely he’s in on it too. It doesn’t matter. Come, the food will get cold. His naan really is very good” and with that he walked off towards the car, knowing that this time I would follow.

I stood there a while in a befuddled daze. I looked towards the pharmacy. The woman was gone. Of course she was gone. She probably ran several different cons. When it comes to small time cons, diversification and frequent relocation are key to success. Con artists who get lazy get caught.

I suddenly realized I had something in my hand and I looked down. I still held the money. I loosened my grip and Red Quaid’s face reappeared in my palm. The orientation of the bill had changed. Quaid was now looking away from me. He looked……..disappointed.

“I’m trying Quaid. I really am. But sometimes it’s hard to be good in this country you created”

Recent Comments